During the 2024-2025 super-election period, Gong noticed a number of ads from electoral candidates that were not labeled as political on social media. Instead, they used categories unrelated to the actual content, such as "law and government", "business", "news, books and publications", or even "health". The essential difference in ad labeling is the amount of information the platforms provide about an ad. For ads marked as political, information about the amount paid for the ad, as well as information about reach and target audiences by gender, age, and location, is immediately available to users. However, for other ads, only information about the estimated number of reached audiences/users is available, without revealing details about price and targeted advertising.

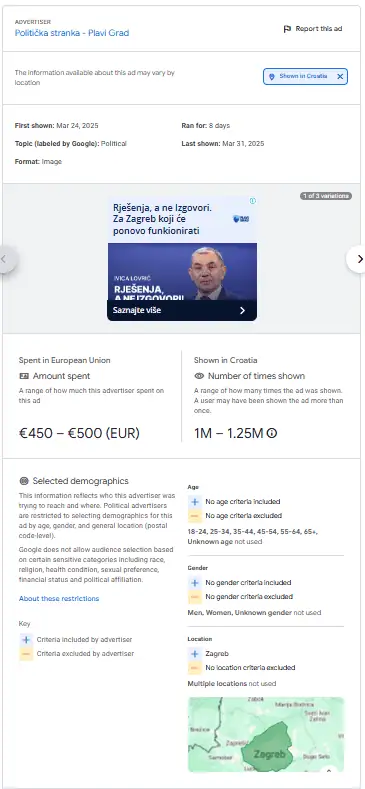

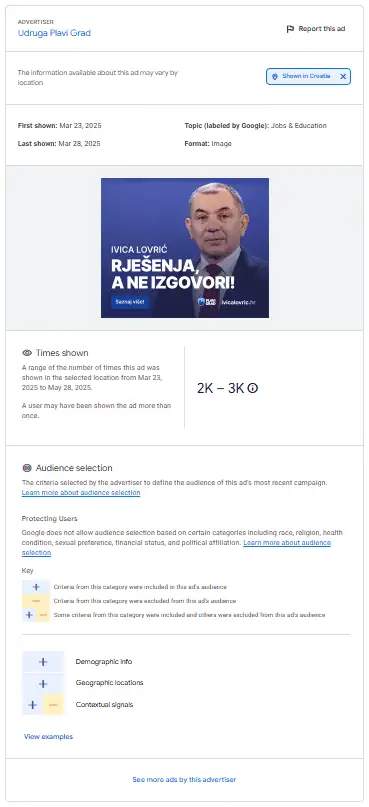

Ahead of the 2025 local election campaign, Gong pointed to one of Zagreb’s mayoral candidates, Ivica Lovrić paid for over 400 ads on Google through the account of his association, Blue City (Croatian: Plavi grad), and had marked only one of them as political. At the same time, he correctly marked the ads on Meta (or the platform correctly recognized and marked the ads as political) and paid for them through the political part. Gong warned about this case back in February, emphasizing that non-transparent advertising of ads leads to the inability to track actual campaign spending, and that paying for ads to a candidate by an association is contrary to the Law on Financing Political Activities.

However, neither Google's self-regulatory mechanisms nor the competent bodies for monitoring campaign costs (the City of Zagreb Election Commission and the State Election Commission) responded to our report. Google did not remove the advertising of Lovrić's ads, even though the content undoubtedly violates the aforementioned regulation, soon entering into force. Even after our report and individual verification of the ads, Google does not consider it objectionable that political content is masked/labeled under prosaic topics. This prevents access to the information that political ads should contain.

The State Electoral Commission, which oversees the regularity of campaign financing, responded to us that it had reviewed our complaint and does not consider that a violation of the law occurred. However, it failed to explain why financing a political campaign with funds from an association is not deemed problematic, even though such a practice is explicitly prohibited by law.

Testing the new regulation of political advertising - platforms do not sufficiently control political candidates

The Transparency and Targeting in Political Advertising Regulation (TTPA), which introduces new rules for more transparent political campaigns and seeks to limit manipulative, covert political ads, begins full implementation in October. In light of the announcements that the largest platforms will abolish political advertising in order to avoid significant fines, we have observed how the option of flagging political advertising and the platforms' self-regulatory mechanisms have been inconsistently applied so far.

Election campaigns on social networks have shown that, despite the existing frameworks on social networks that should make political advertising more transparent, political actors often lack the will (or knowledge) to clearly label their ads, and the platforms themselves. Their control should include artificial intelligence, algorithms, and/or moderators that monitor these ads, do not conduct systematic monitoring of ads, and even when checked, self-regulatory mechanisms have shown major shortcomings in identifying political ads.

The European Union has been increasing pressure on platforms to regulate political content for years. So, Meta introduced advertiser verification, the "paid by..." label, a public Ad Library, and, later, additional transparency tools in 2018 after the scandal with Cambridge Analytica. Google introduced similar measures in 2019, and already in 2020, limited microtargeting to age, gender, and location, while data on political ads is publicly available through the Transparency Report and the Ads Transparency Center.

Despite adapting to European pressures for more transparent campaigns over the years, Google was the first to announce at the end of last year that it was withdrawing from political advertising in the EU, stating that the new rules would make compliance with the regulation practically impossible and risky. The same decision was confirmed by Meta this summer.